In the thousands-of-years-long cultural river of China, classical gardens are not only treasures of architectural art but also a concrete expression of the Chinese philosophy of life and aesthetic pursuit. Guided by the core principle of “Man-made yet seemingly natural,” they integrate mountains, rivers, plants, pavilions, terraces, and poetic artistic conception, creating a spiritual home that combines natural charm with humanistic heritage. As a unique school in world garden art, Chinese classical gardens were inscribed on the UNESCO World Heritage List in 1997, hailed as “the culmination of Eastern gardens.”

![图片[1]-Chinese Classical Gardens - Treasures of Eastern Garden Art World Heritage Introduction](https://www.dgcity.com/wp-content/uploads/2026/01/image-86-1024x490.png)

The origin of Chinese classical gardens can be traced back to the “you” (hunting Parks) in the Shang and Zhou dynasties, initially serving as hunting and entertainment venues for emperors and nobles. After going through the imperial gardens of the Qin and Han dynasties, literati gardens of the Wei, Jin, Southern and Northern Dynasties, the mature prosperity of the Tang and Song dynasties, and the ultimate flourishing of the Ming and Qing dynasties, they gradually formed a complete garden-making system. Divided by the owner’s identity and functions, they mainly fall into two categories: imperial gardens and private gardens. Though distinct in style, they share the same origin and together interpret the essence of Eastern garden design.

![图片[2]-Chinese Classical Gardens - Treasures of Eastern Garden Art World Heritage Introduction](https://www.dgcity.com/wp-content/uploads/2026/01/image-84.png)

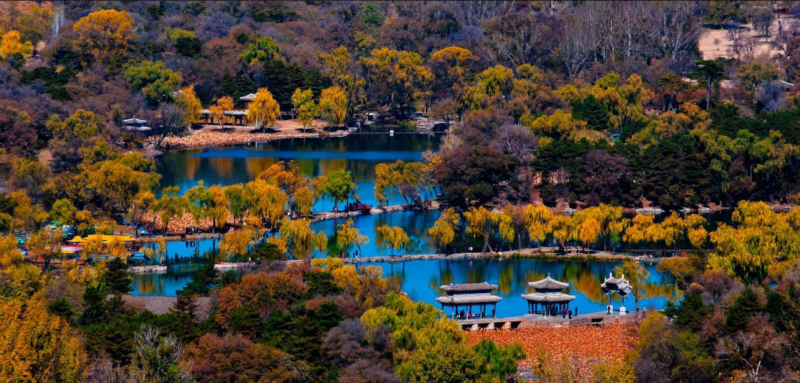

Imperial gardens are renowned for their grand scale and majestic momentum, mostly located in quiet landscapes with beautiful mountains and rivers, integrating political symbolism and living needs. Typical examples include the Summer Palace in Beijing and Chengde Mountain Resort in Chengde. Facing Kunming Lake in the front and leaning against Longevity Hill in the back, the Summer Palace perfectly combines the grace of Jiangnan water towns with the solemnity of northern palaces. Landscapes such as the Long Corridor with colorful paintings, the Tower of Buddhist Incense, and the Seventeen-Arch Bridge are scattered in an orderly manner, bearing the functions of imperial sacrifices and governance while displaying the vivid beauty of natural landscapes. Chengde Mountain Resort, with its layout of “surrounded by mountains and embraced by water, scattered in an orderly way,” integrates the exquisiteness of Jiangnan gardens with the grandeur of northern scenery. Lakes, grasslands, and mountains in the resort set off each other, becoming an important place for emperors of the Qing Dynasty to escape the summer heat, handle government affairs, and connect with ethnic minorities.

![图片[3]-Chinese Classical Gardens - Treasures of Eastern Garden Art World Heritage Introduction](https://www.dgcity.com/wp-content/uploads/2026/01/image-85.png)

Private gardens, characterized by their delicacy and profound artistic conception, are mostly distributed in the Jiangnan region, such as Zhuozheng Garden, Liuyuan Garden, and Wangshi Garden in Suzhou, serving as carriers for literati and scholars to cultivate their moral character and place their feelings. As a model of Chinese private gardens, Zhuozheng Garden takes “water” as its core, with pavilions, terraces, and verandas all built along the water. Winding corridors, leaking windows for framing scenery, expand the limited space into an infinite artistic conception. Landscapes such as “Who Will Sit with Me Veranda” and “Little Flying Rainbow Bridge” not only conform to the aesthetic taste of literati but also imply the philosophy of “harmony between man and nature.” Liuyuan Garden is famous for its “rock stacking” art. Craftsmen stack lake stones to simulate the shape of strange peaks and steep mountains, matching with winding corridors and virtual-real interlaced courtyards. Every step presents a different scene, and every scene conveys a different emotion, making people linger in the picture scroll intertwined with nature and humanities.

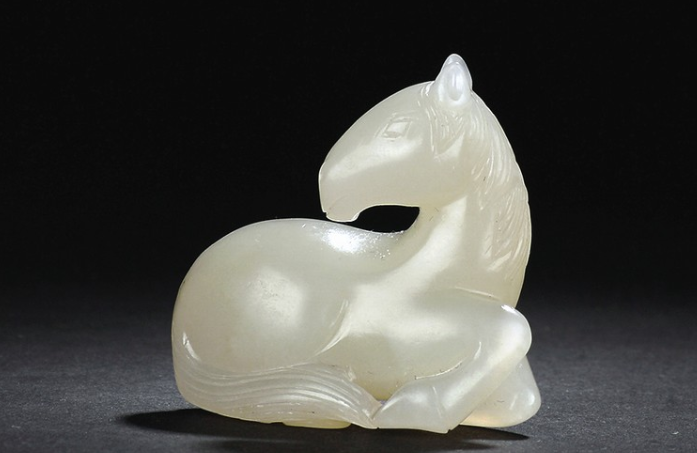

The exquisiteness of garden-making art is the soul of Chinese classical gardens. The four major elements—rock stacking, water arrangement, architecture, and flowers and trees—echo each other, forming a complete garden system. Rock stacking emphasizes “thinness, transparency, leakage, and wrinkling,” simulating the momentum of mountains and rivers with natural lake stones to create a condensed beauty of “a fist standing for a mountain, a spoon representing water.” Water arrangement pursues the natural state of “winding water around corridors, clear springs flowing over stones,” either introducing living water into the garden or building pools and islands, making water the link connecting various landscapes. Architecture emphasizes harmony with nature; pavilions, terraces, buildings, and verandas are all built according to local conditions, not seeking symmetry but complementing mountains, rivers, flowers, and trees. They not only provide places for people to rest and enjoy the scenery but also become the finishing touch in the garden. The selection of flowers and trees takes into account the changes of the four seasons and cultural implications: plum blossoms, orchids, bamboos, and chrysanthemums symbolize the character of a gentleman; pines, cypresses, and bamboos represent perseverance. Peach and plum blossoms bloom in spring, lotus flowers sway in summer, sweet-scented osmanthus fragrances fill the air in autumn, and plum blossoms bloom proudly in winter, making the garden have scenery in all seasons and sentiment in every step.

![图片[4]-Chinese Classical Gardens - Treasures of Eastern Garden Art World Heritage Introduction](https://www.dgcity.com/wp-content/uploads/2026/01/image-87.png)

Beyond visual beauty, Chinese classical gardens contain profound cultural connotations. Literati and scholars integrated poetry, calligraphy, painting, and music into garden design, placing their feelings in plaques, couplets, and inscriptions, making gardens “three-dimensional poems and silent paintings.” For example, the “Rain Listening Veranda” in Zhuozheng Garden combines the sound of rain hitting plantains with the leisure of literati, creating an elegant and distant artistic conception. The “Moon Arrival and Wind Blowing Pavilion” in Wangshi Garden allows people to lean on the railing to watch the moon and feel the breeze, fully showing the realm of “harmony between man and nature.” This garden-making concept that combines spiritual pursuit with natural landscape makes Chinese classical gardens surpass the simple function of rest places and become the sustenance of the Chinese spiritual world.

Today, Chinese classical gardens still exude unique charm. They are not only important carriers of Chinese Culture but also vivid examples of harmonious coexistence between man and nature. Walking into a classical garden is like traveling through thousands of years of time, feeling the elegance of literati among pavilions and terraces, and understanding the true meaning of nature in mountains, rivers, flowers, and trees. This timeless aesthetics and wisdom also provide valuable references for contemporary garden design and ecological protection.

暂无评论内容